八月城隍祭典

為提供使用者有文書軟體選擇的權利,本文件為ODF開放文件格式,建議您安裝免費開源軟體 ([連結])

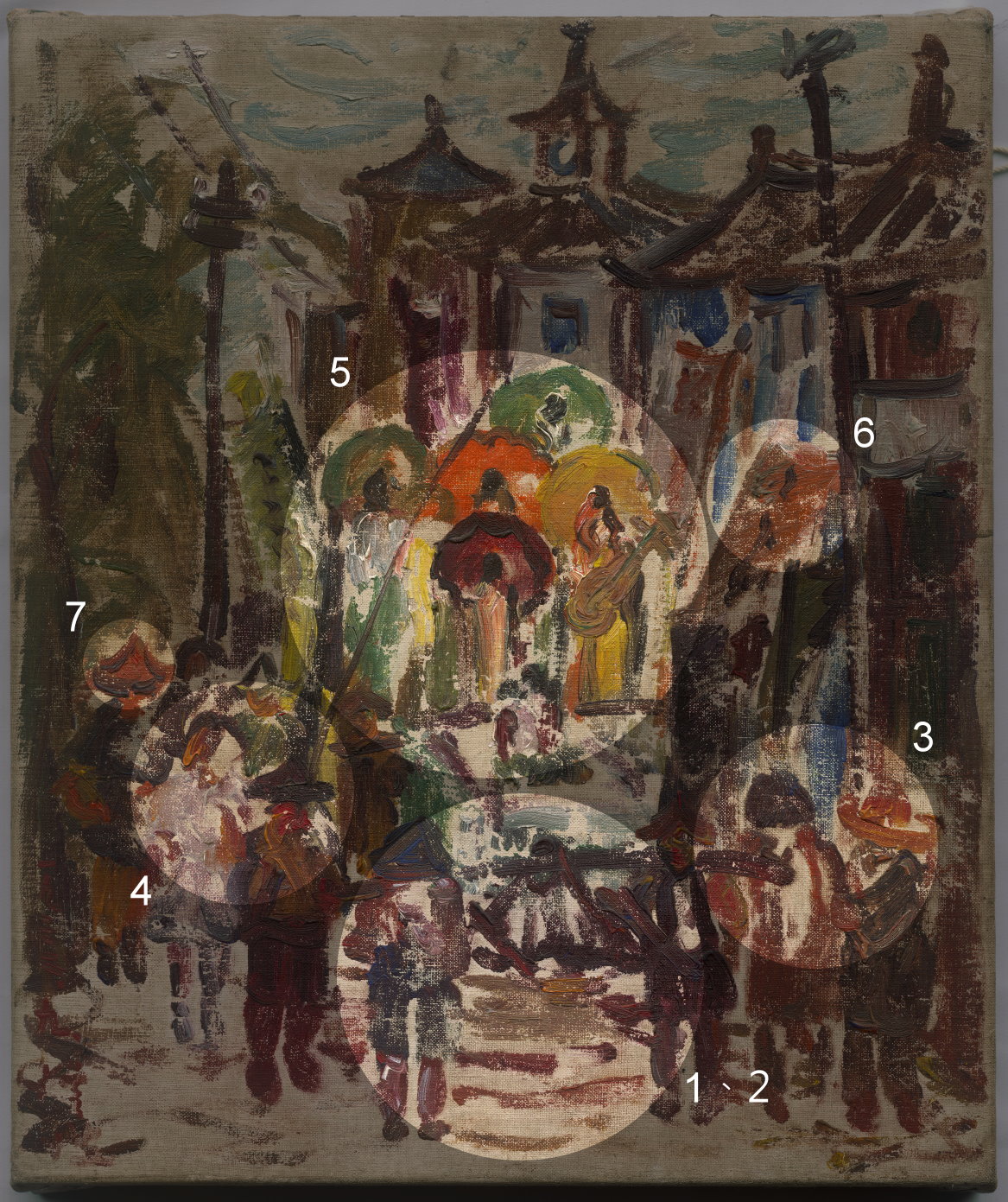

八月城隍祭典

City God Festival in Lunar August

八月城隍祭典

1932, 畫布油彩, 44.8×38.2cm

oil on Canvas

画布油彩

紅色、黃色、橙色、綠色……熱鬧滾滾的遊行隊列走進了畫布當中,轉化成五彩繽紛的色塊,我們彷彿也能夠從混雜紛亂的線條裡,感受到街上的人群雜沓與金鼓喧囂。

Rollicking groups of performers parade into the center of the canvas, which has been transformed into a profusion of colors—red, yellow, orange, and green. Looking at the chaotic mingled shapes, we can almost feel the bustling of the crowd and hear the cacophony of percussion instruments and voices.

赤色、黄色、橙色、緑色…にぎやかな祭りの隊列がキャンバスに入り込み、カラフルな色の塊へと移り変わっていきます。雑多に交わる線からも、街を埋め尽くす人の群れや打ち鳴らされる打楽器の喧騒が聞こえてくるようです。

自1929年遠赴上海教書的陳澄波,若趁著暑假返鄉,總會碰上每年八月初的城隍遶境。對他而言,這場民俗文化的盛典是故鄉的代表性風景,也是他必定不會錯過的創作主題。

In 1929, Chen Cheng-po left for Shanghai to teach art, but sometimes returned home for summer vacation, in which case he could experience the City God Inspection Tour that took place each year at the beginning of the eighth lunar month. To Chen, this grand ceremony was a symbol of his hometown and the local folk culture. It was also, of course, an excellent subject for his paintings.

1929年から上海で教職に就いていた陳澄波が夏休みに帰郷すると、ちょうど毎年8月初めに開催される「城隍遶境」の時期でした。陳澄波にとって、この民俗文化の盛典は故郷を代表する風景であり、見逃せない創作テーマの一つでもありました。

1.城隍

The city god

城隍

「城隍」是城市的守護神,也掌管陰間司法。在清代臺灣,每當新的府、縣、廳成立之後皆會奉祀城隍,擘建於1715年的嘉義城隍廟也屬同樣的例子。日治以後,這座前朝的官設廟宇受到民間的繼續支持,迄今仍護佑著嘉義百姓。

The city god is the guardian spirit of a municipality and administers justice in the netherworld as well. During the Qing Dynasty, each time a new prefecture, county, or township was founded, a temple or shrine would be erected at which villagers could pay their respects to the guardian spirit. As an example, construction of Chiayi’s City God Temple began in 1715 following the founding of the county. During Japanese rule, the temple—a relic of a former power—continued to receive support from local residents. And to this day, the people of Chiayi are blessed and protected by their city god.

町の守り神である「城隍」は冥府の法を司る神でもあります。清代の台湾では、新しい府や県、庁が成立する度に城隍神が祀られました。1715年に建立された嘉義城隍廟もそのうちの一つです。日本による統治が始まってからは、前代政府により建立されたこの廟は民間で維持・管理されるようになり、今もなお嘉義の人々を見守っています。

2.祭典

The ceremony

祭典

在臺灣許多地方,「迎城隍」都是一大盛事。嘉義的城隍祭典是在1908年由地方紳商倡議,仿效臺北霞海城隍廟舉行年度遶境儀式,促進地方繁榮。日治中期,隨著嘉義木材業的迅速成長,木材商人也逐漸成為祭典的有力支持者。

In several different locales across Taiwan, there are elaborate ceremonies to welcome the city god. In 1908, gentry and wealthy merchants from Chiayi proposed following the example of Taipei’s Xia-Hai City God Temple and holding an annual inspection tour to create greater local prosperity. The Chiayi City God Festival was thus initiated. With rapid growth of the local lumber industry during Japanese rule, lumber merchants gradually became strong supporters of the ceremony.

「迎城隍」の祭典は台湾各地で盛大に行われます。嘉義で行われる城隍廟の祭典は、地元の紳商の提議により1908年から開催されています。台北の霞海城隍廟で毎年開催される遶境(巡礼)の儀式に倣い、地方の活性化を目的としています。日本統治時代中期、嘉義の木材業が急成長するに従って、木材商も祭典の有力な後援者となりました。

3.遶境

Inspection tour

遶境

「遶境」指的是信徒將神像迎出廟宇、巡行境內各地的宗教活動。民間觀念裡,神明的訪視可以淨化邪祟,平息瘟疫流行。傳統時代,遶境是鄉里民眾總動員的大事,這個集體參與的過程,也強化了居民的社區意識與地方認同。

An “inspection tour” refers to a religious ceremony in which believers parade the statue of a deity out of its temple and throughout the territory over which that god serves as protector. According to popular belief, a visit from the god can purify evil spirits and quell the spread of disease. In the past, inspection tours were important occasions which mobilized the whole community, strengthening social ties and cultivating local identity.

「遶境」とは、その廟の信徒が神像を神輿にのせ、周辺地域を巡行する宗教活動のことです。民間では、神様が巡視することによりその場が浄化されて厄払いでき、疫病の流行も防げると考えられています。伝統が重んじられていた時代、「遶境」は地域住民が総動員される一大行事でした。この行事に地域が一丸となって取り組むことにより、住民たちの地元意識やローカルアイデンティティも強化されたのです。

4.盛況

A grand occasion

盛況

嘉義城隍的遶境一年比一年熱鬧,到了1930年代,從各地前來參與這場盛會的民眾甚至達到十萬人之譜。隨著規模的持續擴大,遊行隊伍的排場也不斷升級,日間的各家藝陣比拼、夜間的館閣音樂演奏,都吸引大批民眾駐足圍觀。

Chiayi’s City God Inspection Tour gathered momentum year after year until by the 1930s the number of participants from near and far reached over one hundred thousand. As its scale continued to broaden, the celebration grew in extravagance. During the daytime, artistic troupes competed to see who could produce the biggest crowd-pleaser, and at night, musical ensembles performed to the audience’s delight. Day and night, crowds stopped to enjoy the show.

嘉義城隍廟の遶境は年々盛んになり、1930年代になると、台湾各地からこぞって参加する人々で十万人に達するほどでした。祭典の規模が大きくなるにつれて隊列による出し物のレベルもあがり、昼間の「芸陣」による技比べ、夜の「館閣」による演奏と多くの人々が足を止めて見物します。

5.藝閣

Floats

芸閣(芸陣/館閣)

數人合力扛起的高臺是常見於各類慶典中的「藝閣」。多由工商團體出資搭建。這類表演常以傳統戲曲或民間故事為主題,並由真人(常是藝旦或兒童)扮裝。日治時期的迎神賽會常舉辦藝閣評選,其裝修工藝也因此不斷進化。

Traditionally, float platforms were lifted and conveyed along the parade route by the combined strength of several individuals. Their construction was often funded by commercial associations and they were featured in various celebrations. Many float-top performances recounted folktales or stories from traditional opera, usually interpreted by children or female entertainers in period makeup and costume. During Japanese rule, folk festivals frequently hosted float competitions; as a result, the decor and artistry of floats continued to evolve.

数人で担ぎあげる高い台車は各種の祭典でよく見られる「芸閣」です。その多くは商工団体が出資して建造したものです。このような出し物は伝統的な芝居や民間に伝わる故事を主題として、人(多くは芸旦か児童)が扮装しました。日本統治時代の迎神賽会では芸閣のコンテストが行われることも多く、飾りつけもますます華やかになっていきました。

1915年一場遊行活動裡的藝閣。

A float appearing in a 1915 parade

1915年に行われた祭礼行列の芸閣。

國立臺灣圖書館授權。

申請授權:國立臺灣圖書館,「日治時期期刊影像系統‧寫真資料庫」,記錄編號:F110181。影像數位檔名:hp_sxt_0748 _132_125-i.jpeg。取得來源:0748 132 臺灣畫報(昭和12年,1937)。網址http://stfj.ntl.edu.tw/cgi-bin/gs32/gsweb.cgi/ccd=WeZV5p/record?r1=30&h1=0

Source: National Taiwan Library, Database of Images from Japanese-era Periodicals, Record number: F110181. Name of digital image file: hp_sxt_0748_132_125-i.jpeg. Retrieved from: 0748 132 Taiwan Pictorial (12th year of Showa’s reign, 1937). Website: http://stfj.ntl.edu.tw/cgibin/gs32/gsweb.cgi/ccd= WeZV5p/record?r1=30&h1=0

申請授權:國立臺灣圖書館,「日治時期期刊影像系統‧寫真資料庫」,記錄編號:F110181。影像數位檔名:hp_sxt_0748 _132_125-i.jpeg。取得來源:0748 132 臺灣畫報(昭和12年,1937)。網址http://stfj.ntl.edu.tw/cgi-bin/gs32/gsweb.cgi/ccd=WeZV5p/record?r1=30&h1=0

6.旗幟

Banners

旗幟

人群後方高高豎起的布旗可能是神明儀仗,也可能是店家廣告。人潮洶湧的遶境是極難得的祭典,企業與商號時常把握機會製作廣告的旗幟或道具,參與在隊伍當中,一方面可以宣傳自家產品,一方面也能為遊行隊伍增添精彩。

Flying high above the crowds were banners bearing the insignia of the city god or inscribed with the advertising slogans of various businesses. The inspection tour was one of the rare celebrations that had the power to attract bustling crowds. Corporations and businesses often seized the opportunity to generate publicity and produced banners and other promotional materials for the occasion. Along the parade route, these banners added bright colors to the scene.

群集の後ろに高々と立てられた旗は神の旗標か商店の広告でしょう。大勢の見物客が押し寄せる「遶境」はめったにない祭典で、企業も商店もこの時ばかりと広告用の幟や器具を製作し、祭りの隊列に参加します。自社製品の宣伝をしながら、祭りの隊列に華も添えます。

7.斗笠

Bamboo hats

斗笠

日治時期,嘉義城隍的遶境通常在舊曆的八月初三、初四舉行。儘管已是夏末時節,北迴歸線上的氣溫仍舊讓人揮汗如雨,從早到晚的遊行活動更是讓參與者難以消受──無怪乎畫中的男人們都要戴上斗笠,以躲開艷陽的襲擊。

During Japanese rule, Chiayi’s City God Inspection Tour normally fell on the third or fourth day of the eighth lunar month. Even though summer was coming to an end, temperatures along the Tropic of Cancer remained uncomfortably high. It was hard to bear the heat on a normal day, let alone throughout a morning-to-night celebration. This perhaps explains why the men in Chen’s painting are all wearing bamboo hats—to block the scorching rays of the sun.

日本統治時代、嘉義城隍廟の「遶境」はたいてい旧暦の8月3日か4日に行われました。季節はすでに夏の終わりですが、北回帰線上はまだ気温が高く、汗が滴り落ちるほど。朝から晩まで町を練り歩く人たちにとっては耐え難く、強烈な陽射しから身を守るために、画中の男性たちが斗笠(笠)をかぶっているのも不思議ではありません。